Der Code

01

> 9.000 Choräle an Trainingsdaten

- Unsere Daten stammen aus

Gregobase, einer akademischen (copyrightfreien) Online-Datenbank für Gregorianische Choräle. - Mit Hilfe eines kleinen Crawlers beziehen wir unsere Trainingsdaten!

name: Ave Maria;

%%

A(cdc) men(bc)Grundlage

Die GABC-Syntax

- Header mit Metadaten (

name:,title:,annotation:). - Musikabschnitt beginnt nach

%%. - Noten werden in Klammern gesetzt; Text davor.

- Sonderzeichen steuern Ligaturen und Neumengruppierung.

- vgl. Gregorio-Project

# Häufige End-Kadenzen

ending_trigrams = Counter()

for seq in train_token_seqs:

if len(seq) >= 3:

ending_trigrams[tuple(seq[-3:])] += 1

common_end_trigrams = [list(k) for k,v in ending_trigrams.most_common(8)]

# Sammelt die am 8 häufigsten vorkommenden letzten 3-Token-Folgen (Trigramme)02

Aufbereitung der Trainingsdaten

- Bereinigung der Raw-Tokens von Metadaten.

- Statistik für das Postprocessing:

- Berechnung der Kirchentonart („Finalis“) für den zu erzeugenden Choral

- Erstellung von Trigramm-(Schlussendungen) und Bigramm-Listen (typische musikalische Fortschreitungen), die im Ergebnis einberechnet werden

03

Trainieren der KI

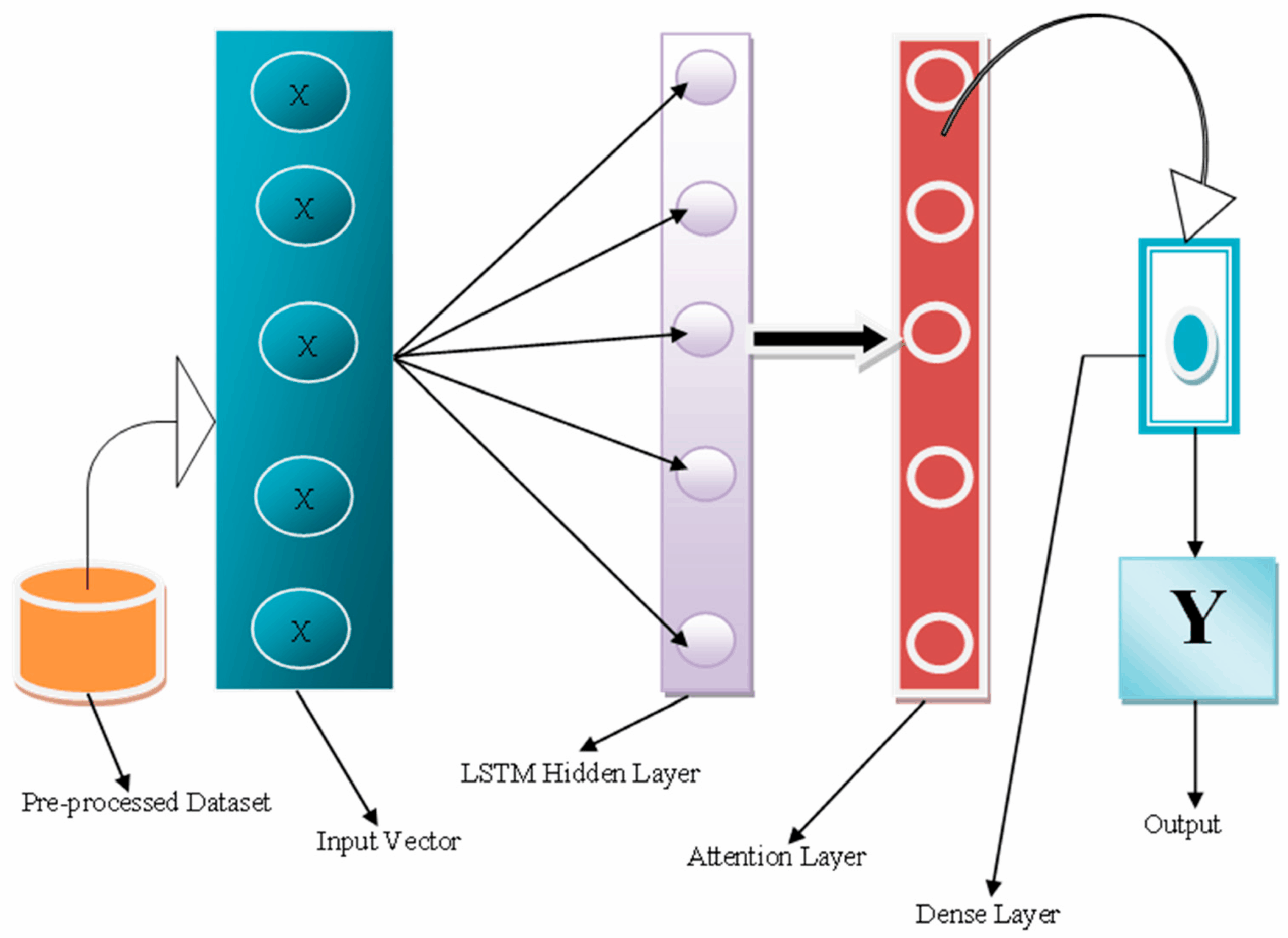

- Wir verwenden ein tokenbasiertes LSTM-Netz:

- Eingaben sind Sequenzen von 40

Tokens, die durch eine Embedding-Schicht (128-Dim) in Vektoren übersetzt werden. - Zwei LSTM-Schichten (512 Units) lernen

04

Postprocessing

- Melisma-Funktion: Bündelt mit variabler Wahrscheinlichkeit mehrere Noten auf eine Silbe → Wie melismatisch soll das Ergebnis sein?

- Bigramm/Trigramm-Sampling: Sorgt für typische Fortschreitungen und einen authentischen Choral-Schluss

- Finalis-Funktion: Beendet Choral mit berechneter Finalis (Schlusston) und definiert damit die Kirchentonart → so kommt echtes „Choral-Flair“ auf

05

Ausgabe

- Das Ergebnis wird als GABC ausgegeben und anschließend gerendert. Jetzt kann Text nach Wahl unter den Choral gelegt werden!

Technische Expertise Dr. Shintaro Seki

First of all, I felt that the overall design of the project was extremely well thought out, and that it was a project made possible precisely because it represents a collaboration between a historically established choir and computer science. By entrusting the interpretation of the score and the production of sound to a choir, who are deeply versed in church music, and limiting the role of the computer to a mechanism for obtaining musically coherent scores, the project adopts a clear division of labor. This not only defines in a compact way the problems that should be addressed by computation, but also succeeds in preemptively avoiding potential criticism or controversy that might arise when approaching religious topics through the use of computers, by preserving the act of choral singing—an activity that can itself be considered religious—within the process.

In ensuring the “authenticity” of the new religious music produced by the project, the participation of the Regensburger Domspatzen, with its history and authority, and the series of procedures through which a sonic image only emerges through human musical practice—namely interpretation and performance—seem to play a crucial role in this undertaking.

On a personal note, I was particularly intrigued by the use of the GABC format in this project. While most contemporary music formats prioritize encoding the "semantic" of a score, GABC adopts a representation rooted in its "visual form." The challenge of balancing meaning (structure) with visuals (form) has been a central debate since the inception of Music Encoding. Although current trends in Digital Humanities favor semantic description for the sake of searchability and interoperability, traditions like neumatic notation—where meaning is dynamically shaped through human interpretation—demand a more flexible approach that goes beyond fixed and determinate encoding.

Much of today’s music information technology has developed under the implicit assumption of the "staff-centric" paradigm and its underlying Western musical theory. However, by treating a non-staff notation as symbolic data and applying AI models to it, this project reveals the latent biases within our current technological ecosystem and offers a pathway to broaden its scope. For music informatics to truly encompass cultural richness, the digitization and analysis of such "open-to-interpretation" ancient notations are indispensable. By illuminating the roots of Western music through AI, this project does more than push technical boundaries; it poses a fundamental question about how computing can embrace the plurality of musical representation. It is a truly ambitious and visionary undertaking.

Hier klicken, um den Inhalt von YouTube anzuzeigen.

Erfahre mehr in der Datenschutzerklärung von YouTube.